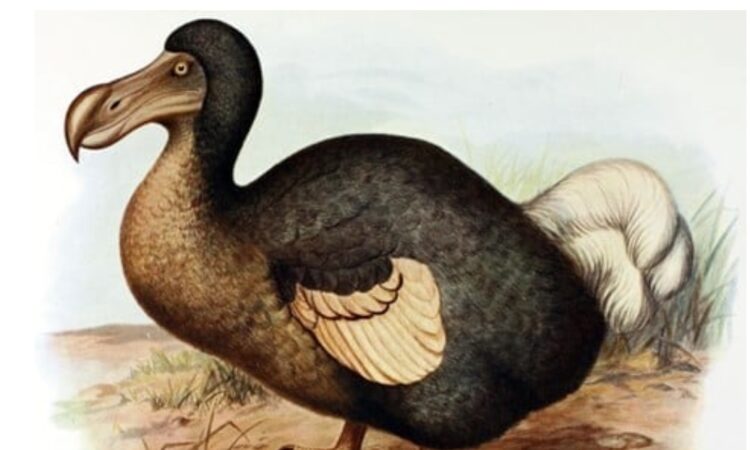

Scientists believe they have found a way to bring back the animal most synonymous with the extinction, the dodo bird. Should their endeavor prove successful, this could open the door for the resurrection of several other animals that were thought to be long gone.

A “de-extinction company” known as Colossal Biosciences has decided to play God and right a “wrong” done by humans by using edited DNA to create a so-called proxy version of the dodo since an exact clone is not possible. Should the recreation prove successful, the next step would be to re-introduce the dodo to its original habitat in Mauritius.

The founders of the company believes reintroducing the dodo will benefit conservation and the wildlife ecosystem. They do not elaborate on why, however.

Colossal Biosciences is also working bringing other endangered species back from the dead, such as the Tasmanian tiger and wooly mammoth.

Here is the story from Vice fully explaining the process for “de-extincting” the dodo and the many challenges Colossal Biosciences faces:

Colossal Biosciences, founded in 2021 by entrepreneur Ben Lamb and Harvard geneticist George Church, announced on Tuesday that it plans to resurrect and rewild the dodo, the iconic flightless bird that has become a powerful symbol of extinction after it was rapidly wiped out as a result of human interference on its native island of Mauritius.

Colossal is already working on efforts to de-extinct the wooly mammoth and thylacine (aka the Tasmanian tiger), and reintroduce them to wild habitats. In the process, the company hopes to pioneer new technologies with applications in conservation biology and human healthcare, to name a few.

Now, the company has added the dodo to its de-extinction wishlist and tapped Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Santa Cruz, to back the project. The team envisions the return of a “proxy” version of this idiosyncratic bird, meaning a species with edited DNA as opposed to an exact clone, to its original habitat in Mauritius.

“I think this is an opportunity where, given the man-made nature of the extinction of the dodo, man could not only bring the dodo back, but also fix what was done to parts of the ecosystem to reintroduce them,” noted Lamm in the same call. “There’s a lot of benefits from a conservation perspective, in terms of what we can learn from rewilding.”

The flightless bird was such a one-off that its closest living relative is the Nicobar pigeon, a colorful flying bird that looks completely different from its famous extinct cousin. The bizarre appearance distinguished the dodo as a cultural curiosity practically from the moment European explorers came across it during the 17th century.

Now, Shapiro and her colleagues are tackling the challenge of stitching together a dodo-like animal using genomes that have been sequenced from real dodo specimens, as well as genomes from their close relatives, such as the Nicobar pigeon and the Rodrigues solitaire, another extinct flightless bird that lived on the nearly island of Rodrigues. Indeed, de-extincting the dodo will have to start with reverse-engineering it.

“Once a species is extinct, it’s really not possible to bring back an identical copy,” Shapiro said. “The hope is that we can use, first, comparative genomics so we can get at least one, and hopefully more, dodo genomes that we can use to look and see how dodos are similar to each other, and different from things like the solitaire.”

From there, the team will “compare those to the Nicobar pigeon, and other pigeons, and identify mutations in that genome that we believe may have some phenotypic impact that made the dodo look like a dodo instead of like a Nicobar pigeon,” she continued.

Getting the right genetic ingredients for a dodo proxy is only the first hurdle in what may be a long scientific quest. The researchers will also have to figure out how to get a dodo embryo into an egg so that a new generation of birds can successfully hatch.

As with many emerging fields, the science of de-extinction contains many ethical nuances in addition to its technical challenges. Tom Gilbert, who serves as director of the University of Copenhagen’s Center for Evolutionary Hologenomics, told Motherboard that proxies for extinct species may well be technically feasible, but that is only the beginning of the conversation.

“The question really is, how close will the proxy be to the extinct form?” said Gilbert, who recently joined Colossal’s advisory board, in an email. “That’s a much harder question, and not straightforward to answer, given it raises the question…what are you measuring? Genomic similarity? Physical similarity? Similarity in the niche it fills/what it does, even if it doesn’t look the same (e.g. if you can make an elephant able to live in the cold where it acts like a mammoth…is that enough??

“For reasons I’ve argued before in various articles I think that the best we can hope for is something that is an equivalent with regard to the niche it fills,” he continued. “This raises the question of is it worth it? Here it’s also not black and white. Sometimes maybe, but in other cases maybe the environment is so changed already that the hope of free living populations is far from what can be done. One has to bear in mind e.g. how much, relatively, human untouched environment is left.”

There are other dilemmas to consider if the dodo were to be resurrected. The first dilemma is how to protect the bird from another extinction.

This will require significant buy-in from the Mauritius government to not just accept the dodo but also a willingness to enact significant penalties against poachers and trophy hunters. Anyone with a brain can envision the enormous value of an iconic species brought back to life.

Even with protection from the government, the “de-extincted” dodo will still face the same challenges from the invasive wildlife that contributed to its extinction in the first place. The crab-eating macaques, rats, cats, and dogs that preyed on the dodo and its offspring remain on Mauritius. The dodo had no defense mechanisms back when it roamed the island.

The second dilemma to ponder is while the dodo poses no threat to humanity, there are other extinct species which could. What is to stop scientists from deciding to make the movie Jurassic Park a reality and attempt to bring back the dinosaurs, for example?

Bringing back long-dead species is fraught with far too many risks to prove worthwhile. Instead, scientists should fully concentrate their efforts on saving current endangered species.