A therapist once explained that constantly commenting on other people’s looks often comes from a desire to feel powerful or superior.

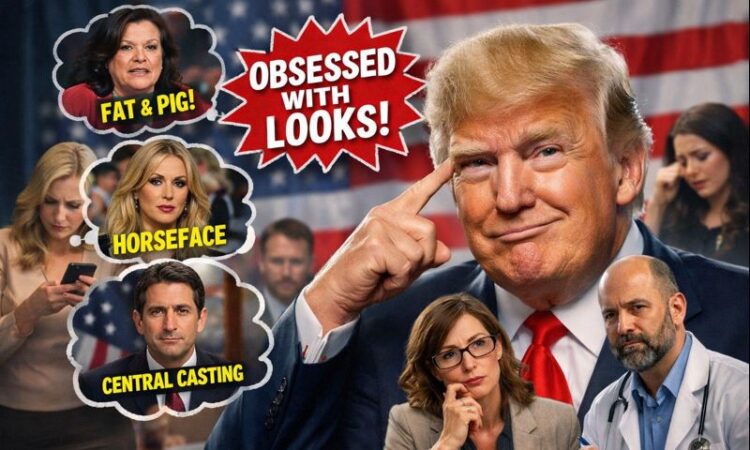

That idea feels especially relevant after Donald Trump announced on Friday that he plans to nominate former Federal Reserve official Kevin Warsh as the next chair of the Federal Reserve. In the announcement, posted on Truth Social, Trump praised Warsh’s qualifications, but he also couldn’t resist commenting on his appearance. Trump said Warsh looked like someone straight out of “central casting,” a phrase he often uses to suggest someone looks perfect for television or public display.

This isn’t new behavior for Trump. Over the years, he has repeatedly commented on how people look, whether they are royalty, judges, military members, or foreign officials. He has used the same language even in disturbing situations, describing a murdered Ukrainian refugee in terms of her beauty and calling the widow of activist Charlie Kirk “beautiful” shortly after her husband’s death.

At the same time, Trump frequently insults people—especially women—based on how they look. He has publicly called Jessica Chastain “not hot,” referred to Stormy Daniels as “horseface,” labeled Rosie O’Donnell “fat” and “a pig,” and described Bette Midler as “extremely unattractive.” These comments are often cruel, dismissive, and meant to humiliate.

While Trump is not the only person who fixates on appearance, seeing this behavior from someone in the highest office in the country raises serious concerns. It leads people to ask what this obsession with looks says about someone’s values and character, and how this kind of language affects society when it comes from powerful leaders.

Mental health professionals say that constantly judging others by their appearance often reflects insecurity and a need for validation. According to licensed social worker Monica Cwynar, people who do this may be trying to assert social dominance or align themselves with society’s narrow beauty standards. She explains that it can show a lack of self-awareness and a reliance on external approval, rather than confidence or emotional maturity.

Another therapist, Panicha McGuire, points out that society itself plays a role. She explains that systems like white supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy have trained people to rank others visually before considering their character or humanity. Standards that favor whiteness, thinness, youth, and able-bodiedness are treated as ideals, and many people internalize the habit of judging worth based on looks.

Because of this, appearance-based comments are often less about the person being judged and more about the speaker’s internal fears, biases, and values. Sometimes it may be an awkward attempt to connect, but more often it reveals insecurity or a worldview that ties human value to how closely someone matches dominant standards rather than who they actually are.

When leaders focus on appearance, the impact goes far beyond individual hurt feelings. Cwynar says it reinforces shallow values across society, especially when men in power comment on women’s looks. It normalizes objectification, encourages harmful stereotypes, and sends the message that appearance matters more than ability, integrity, or competence.

This kind of messaging can be especially damaging to young people. Constant emphasis on looks—amplified by social media and television—has been linked to lower self-esteem, increased anxiety, and body image struggles among teenagers. When leaders behave this way, it reinforces the idea that self-worth depends on how you look.

McGuire adds that this behavior also encourages dehumanization. When leaders reduce people to their appearance, it shifts attention away from real issues like policy, accountability, and justice. It teaches people that those who don’t fit narrow ideals deserve ridicule or exclusion, rather than empathy or respect.

Licensed therapist Joshua Terhune agrees, saying that reducing people to their looks erodes empathy and teaches younger generations to do the same. He notes that social media is filled with compilations of Trump insulting people, often treated as entertainment, even though the behavior itself is deeply dehumanizing.

On a broader level, this obsession with appearance can even affect who gets power. In Trump’s administration, critics argue that prioritizing image and loyalty over competence has led to unqualified—and sometimes dangerous—individuals being placed in key government roles.

On a personal level, focusing on appearance shapes how people see themselves and others. Cwynar explains that it encourages shallow relationships and fuels bias, taking a serious toll on mental health. Women, in particular, are judged more harshly based on looks, which can lead to anxiety, depression, and chronic self-doubt. Men are also pressured to meet rigid ideals of masculinity and attractiveness, often leading to isolation and emotional distress.

McGuire points out that appearance-based judgment affects different groups in different ways. Women are valued or dismissed based on attractiveness. Black people are policed for their hair and bodies. Asian women are exoticized. Disabled people, people of size, and neurodivergent individuals are frequently stigmatized. These attitudes don’t stop at social interactions—they influence systems like health care, where people who don’t fit “ideal” bodies are more likely to be dismissed or misdiagnosed.

Despite how common this habit is, experts say it can be unlearned. McGuire suggests starting by noticing the impulse to comment on appearance and questioning where it comes from. Instead of focusing on looks, she encourages naming qualities like kindness, intelligence, humor, or creativity. Compliments about appearance aren’t always harmful, she says, but they become a problem when they dominate how we relate to others.

Cwynar echoes this, recommending mindfulness and intentional language shifts. She encourages people to surround themselves with communities that value depth over surface-level judgment and to speak openly about the harm caused by appearance-based comments. Practicing self-compassion and affirming one’s own worth can also help counter social pressure.

Terhune offers a simple rule he calls the “30-second test.” If someone can’t fix something about their appearance in 30 seconds or less, don’t comment on it. Weight changes, tiredness, or physical traits don’t need to be pointed out. But if someone has food in their teeth or an untied shoe, that kind of comment may actually be helpful.

When dealing with people who constantly judge others by their looks, Terhune suggests redirecting the conversation or setting clear boundaries. Saying something like, “I’m trying to focus less on appearances—it’s better for my mental health,” can be enough. And if someone keeps pushing, a more direct response may prompt them to reflect on why they’re so focused on how others look.

Ultimately, breaking the habit of leading with looks means choosing empathy over judgment and humanity over shallow standards.