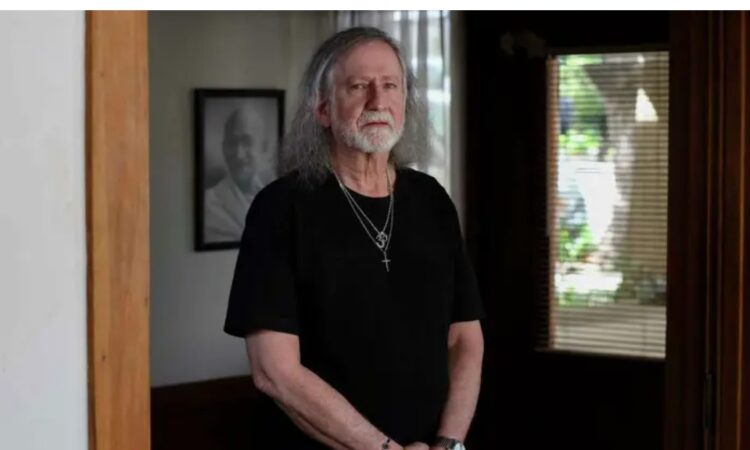

Two decades ago, Tom Rudderow underwent spinal fusion surgery. At first, it appeared all had gone well. As he healed, however, his pain persisted. His surgeon eventually diagnosed him with arachnoiditis, an incurable disorder that, he was told, would cause him a lifetime of suffering.

“I remember this surgeon coming into the room crying,” Rudderow told me over the phone last week, from his home in Oakland. “He said, ‘The only thing you can do is take painkillers, there’s nothing else that will help you with this.’ ”

That diagnosis has rung true. Without his medication, Rudderow told me, he can’t even walk. So, for 20 years, he’s taken morphine daily in order to function.

But that freedom to exist without pain is now under threat.

In December, he stopped by his Kaiser pharmacy to pick up his monthly prescription and noticed something was amiss. He was forced to wait two hours for his pills. When he received them, there were fewer than his doctor had prescribed. The pharmacists told him that going forward, he will be given fewer pills each month.

Rudderow’s doctor had not authorized the tapering of his drugs and received no warning of the plan.

It felt like I was being treated like a drug addict,” Rudderow said.

He isn’t alone. Over the past few months, similar tales have emerged of a growing crisis at the pharmacy counter. Some pharmacies are cracking down on prescriptions where the doctor and patient are in different ZIP codes, while others are refusing to fill prescriptions without clear diagnoses from doctors.

The goal in all of this, ostensibly, is to reduce opioid abuse. In San Francisco, nearly 6.4 million doses of opioids were filled just through Walgreens pharmacies from 2006 through 2020. Many of those prescriptions came from doctors with suspended licenses. Overdoses skyrocketed, and we still see the impact of addiction on our streets today.

For too long the lever of oversight was in the “off” position. Now, it’s finally switched to “on.” But evidence suggests we’re overcorrecting, and people are suffering as a result.

That increased oversight finally started this past year, after pharmaceutical distributors settled lawsuits with 46 states for $26 billion over their role in the overdose epidemic. Those distributors — AmerisourceBergen, McKesson and Cardinal — are the largest in the country.

They have created opaque algorithms for the pharmacies they serve. If an outlet hits its cap for, say, morphine, it will be cut off. Any clients in need of that medication will then have to go elsewhere. But there’s no transparency around what that cap is.

When I reached out to Cardinal and AmerisourceBergen, they directed me to a statement from the Healthcare Distribution Alliance that kicks the blame up the chain of command. “The DEA historically has provided only limited guidance on what constitutes a suspicious order. In absence of clear, industry-wide guidance, distributors have crafted their own programs to detect and report orders that are of unusual size, frequency or pattern.”

In addition to these mysterious distributor guidelines, a decade-old policy called the “good faith dispensing policy checklist” is being enforced more strictly at many pharmacies, particularly Walgreens. It requires pharmacists to triple-check prescriptions for controlled substances. One pharmacist I spoke to, who works in compliance, told me she heard the Drug Enforcement Administration plans to do surprise visits at pharmacies this year, spurring many companies to more rigorously examine the prescriptions they’re handing out..

At face value, this is a good thing. A doctor I interviewed says she appreciates when a pharmacist calls her to inquire if she knew about a medication on a patient’s chart that negatively interacts with one she’s prescribed, for example. When done well, oversight can lead to better patient care. But there’s a difference between cracking down on the corporate greed that resulted in the prescription opioid epidemic and instituting rules so strict and time-consuming that patients can’t access the drugs they legitimately need.

We are absolutely failing to hit a happy medium.

This sweeping enforcement crackdown extends beyond opioids. Buprenorphine, a pain medication used to help wean people off opioids, is on this list, as is Adderall, a drug used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder that is already plagued by supply shortages.

Drug distributors are defensive, pharmacists are stressed, doctors are confused. And the impact on patients is enormous.

Rudderow is doing everything he can to find alternatives to his prescription pills. He signed up for a pain clinic at Kaiser, where he receives physical therapy and takes meditation classes.

“I hate that I have to use this stuff, but I hate more that it’s being taken away,” he said of morphine. .

Rudderow has written a letter to Kaiser, asking them to keep his prescription intact until he can find another method to address his chronic pain. But he’s received no substantial response.

“The silence I’ve received just makes the fear and confusion more intense,” he said. “I have no idea what’s going on because it seems no one has any idea what’s going on.”

At 68 years old, he’s now considering options he’d never thought he would.

“I never thought much about euthanasia,” he told me. “But I know what it’s like to be in so much pain that you can’t function, and if they put me in that position, I’m not going to want to be here.”