Sixty years after the Voting Rights Act was passed to protect Americans—especially Black voters—from discrimination, the law is being stripped of its power. Courts, once a place where people could challenge unfair voting rules and hold leaders accountable, are becoming harder to access.

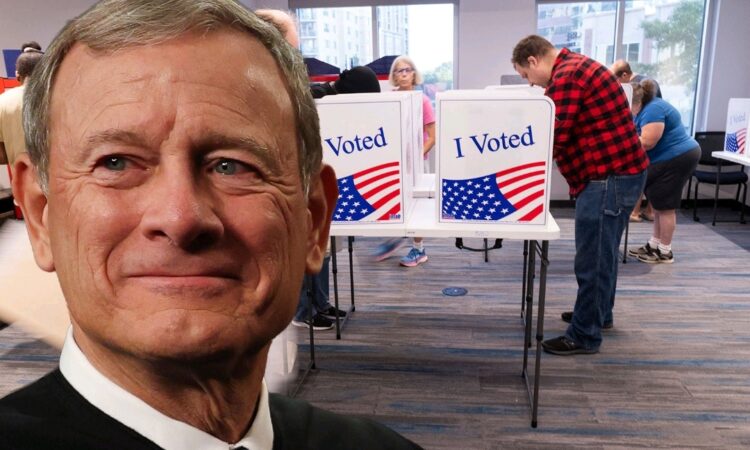

The biggest setback came in 2013, when the Supreme Court’s decision in *Shelby County v. Holder* removed the rule that required certain states and local governments with histories of discrimination to get federal approval before changing voting laws. Chief Justice John Roberts said racial discrimination in voting had largely been solved, but Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg warned that ending the rule was like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you’re not getting wet.”

Without that protection, states quickly moved to pass restrictive laws. Texas reinstated a strict photo ID rule that had been blocked for discriminating against Black and Latino voters. North Carolina passed a law cutting early voting, ending same-day registration, and adding ID requirements—changes later struck down for targeting Black voters “with almost surgical precision.”

The Supreme Court weakened voting protections again in *Brnovich v. DNC*, making it harder to prove racial discrimination and giving states more freedom to pass restrictive laws as long as they claim they’re protecting “election integrity.” Laws like Georgia’s SB 202, passed after Trump lost in 2020, have since reduced voting access, especially for Black voters.

Now, the Court may go even further by limiting who can bring lawsuits under the VRA’s Section 2, which is currently the main tool left to challenge voter suppression. Some federal courts have already ruled that only the U.S. attorney general—not private citizens or civil rights groups—can file these cases. If the Supreme Court agrees, most challenges to discriminatory voting laws would die before they begin, especially under administrations unwilling to act.

At the same time, the Trump administration has removed career voting rights lawyers, backed away from enforcement, and supported laws like the SAVE Act, which would make voter registration harder by requiring certain government documents that millions don’t have.

Voting rights have shifted from obvious barriers, like literacy tests, to more subtle ones—bureaucratic hurdles, confusing paperwork, fewer voting locations, and frequent rule changes. These tactics still take a toll, especially on communities of color, but are harder to fight in court as legal protections weaken.

Sen. Raphael Warnock has reintroduced the John Lewis Voting Rights Act to restore key VRA protections, stop unfair voter purges, and allow individuals to keep suing in court. But for now, much of the responsibility to protect democracy is falling on individual voters—something the original VRA was meant to prevent.

On the 60th anniversary of the law, the country is drifting back toward a time when access to the ballot box depends on endurance, privilege, and luck—rather than being a guaranteed right for every citizen.