In our modern world of red tape and records, what happens to a person after they’ve shuffled off this mortal coil is pretty standard. (Most of the time, at least, it’s exceptions that make the rule.) That wasn’t always the case, and in the old Wild West things could get pretty dodgy.

One of the most infamous cases of a bizarre, post-mortem journey is the oft-told tale of Elmer McCurdy. He wasn’t exactly super famous in life, but he was in death: A lot of people saw him, at least, because his earthly remains spent some time as an attraction in a funhouse.

McCurdy was a terrible safecracker and train robber who was killed in a police shootout, and when no one claimed his remains, the funeral director went above and beyond in preserving him … so he could use him to advertise his business. From there, he proved to be such an impressive specimen that he eventually got sold into the sideshow circuit.

It wasn’t until 1977 that his arm was accidentally pulled off by workers at the haunted house. It was there that he’d suffered the final indignity, painted to glow in the dark and strung up from a noose. Once they realized it was, in fact, all that was left of an actual person, he was given a proper burial. There’s actually one more footnote to his story, but since it ties into the fate of another Wild West outlaw, let’s talk about other earthly afterlife journeys.

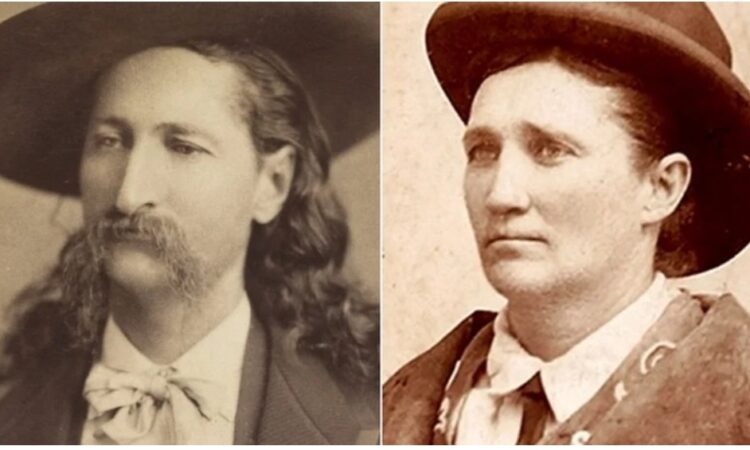

According to the research done by retired Dakota Wesleyan University history professor James D. Laird, Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane were not actually a couple, as is often reported. McLaird explained to Wild West (via HistoryNet): “… even Calamity only claimed in ‘Life and Adventures of Calamity Jane, By Herself,’ that she and Wild Bill were friends.”

Rumors of a romantic relationship were seemingly supported by what happened after Hickok’s death. Famously killed by a bullet to the back while mid-card game — and while holding the aces-and-eights that would become known as the Dead Man’s Hand — Hickok was buried in Deadwood’s original cemetery, Ingleside, but that’s not the place he’s resting he’s in now.

Deadwood historic preservation officer Kevin Kuchenbecker told the Mitchell Republic that in 1879, three years after his initial burial, Hickok was exhumed and reinterred in a new cemetery just outside Deadwood called Mount Moriah. A decade later, his gravesite had become such a major tourist attraction that his tombstone was destroyed by souvenir hunters in short order. Kuchenbecker says it was the tourism aspect that’s at the heart of those Calamity Jane rumors. When she died in 1903, she was buried beside Hickok. It wasn’t out of any romantic connection, though, as Kuchenbecker explained: “Part of it was not only out of respect for a legend in her own time, but if you put two legends side by side? It’s a draw.”

Dentist-turned-gunslinger Doc Holliday, a close associate of Wyatt Earp, died in bed at the Hotel Glenwood in Glenwood Springs, Colorado in 1887. (His famous last words, “This is funny,” were an invention of an author 40 years later, according to “The World of Doc Holliday: History and Historic Image.”) That’s just a hop, skip, and a jump from the Linwood Cemetery, which is where history buffs can finish off their Holliday retrospective with a visit to a memorial marker. Only, that’s not where he’s buried.

Holliday died penniless and was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in the cemetery’s Potter’s Field. That means there’s no actual grave marker or tombstone, and since it wasn’t recorded exactly where he was buried, that’s left the story ripe for rumors. Some say, his final resting place wasn’t in that cemetery at all

Holliday was originally from Georgia, and there is a perfectly plausible belief that he may actually have been returned to his home and buried alongside his father, who was a wealthy landowner and politician.

This theory suggests that although Holliday’s later misdeeds estranged him from his parents and made it impossible for them to bury him in the family plots and maintain their Southern respectability, arrangements were made to return his body to Georgia and bury him alongside his father in secret. (It’s also theorized that his father made the trip from Georgia to Colorado and back himself.) And there’s an intriguing bit of support for that: His father doesn’t have a tombstone, either. Is it to keep his son’s remains safe from gravediggers and souvenir hunters?.

Everyone who knows anything about the Wild West knows that Butch Cassidy (right) and the Sundance Kid (left) ultimately died in a shootout with Bolivian law enforcement. But there’s a massive catch: The two bodies were never actually identified by anyone who knew what the outlaws looked like, no photos were taken, and when they were buried in the San Vicente cemetery, the locations were never marked publicly or in law enforcement records.

That’s given rise to the story that Cassidy, at least, survived to reboot his life into something more law-abiding and to live to a ripe old age. His sister, Lula, said as much, claiming he died in Washington State and was buried in a secret location. Was he? There’s actually not much to say that he was or that he wasn’t.

Interestingly, in the 1990s, historians Daniel Buck and Anne Meadows found a man living in San Vincente who said that his father had been the one to bury the two outlaws. The story was passed down to him, and when the researchers finally tracked him down, he said (via The Washington Post), “Why did you take so long to get here?” He was able to direct them to the burial location and when the grave was exhumed, there were, in fact, two men buried there. Butch and Sundance? According to DNA testing, no. For now, rumors — including Sundance’s possible burial in Utah and Cassidy’s in Nevada — continue

Annie Oakley was born in 1860 and was already a sharpshooting expert by the time she was a teenager. She used her skills to hunt and support her family after the death of her stepfather, and in 1875, she was invited to take part in a Cincinnati competition. It was there that she defeated reigning sharpshooting champ Frank Butler in a close-call, final-shot match-up that sounds fictional but is absolutely true. Then, instead of sulking about being beaten by a girl and nursing his damaged masculinity, Butler married her.

Oakley and Butler traveled and performed together for about the next five decades, and when Oakley died in 1926, the heartbroken Butler passed away just 18 days later. They were buried in Oakley’s native Ohio, and laid to rest on the same day in Brock Cemetery near Greenville.

But here’s where the rumors come in. Both Oakley’s and Butler’s graves are very obviously marked, but according to “Central Ohio Legends and Lore,” legend has it that when the couple was buried on Thanksgiving Day in 1926, her ashes were interred not behind her own headstone, but with him in his coffin.

Geronimo surrendered to American military forces in 1886, and — now a prisoner of war — would be moved to Oklahoma’s Fort Sill in 1894. When he died of pneumonia, it was 1909, and he’d been a prisoner for 23 years.

A section of Fort Sill was set aside as an Apache cemetery, and that’s where Geronimo was laid to rest. It was highly controversial, though, and The Oklahoman reported on the three sides to the story way back in 1982. On one hand, he was going to stay right where he was, because. On another, he made no secret of wanting to return to Arizona, and some campaigners believed that’s what needed to happen. But other Apache believed he needed to stay: As Rose Chinney (a descendant of Geronimo’s) explained, “The question goes back to tribal customs, and you don’t dig up remains.”

However, that may have already happened. In 2009, The New York Times reported Geronimo’s heirs were suing over the long-held Yale tradition that claimed Prescott Bush led a group in the desecration of Geronimo’s grave, stealing his skull, several bones, and several artifacts. After their removal, they were reportedly installed in a display in the headquarters of the Skull and Bones society. Discovered documents seemed to support that, and the lawsuit asked for either proof that it hadn’t happened, or confirmation that it did — and, in that case, the return of the bones. The lawsuit was dismissed, as it was ruled that Geronimo’s remains were too old to be protected by the cited laws.

John Wesley Hardin dropped dozens of bodies, killing his first man when he was 15 and earning the nickname “Little Arkansas” from Wild Bill Hickok. After a murder conviction, he went on to become an attorney and attempted to run for public office. Fast forward a bit to 1895, and in the midst of trying to set up his own law practice, he was shot and killed by El Paso law enforcement. (Circumstances were unclear, but given that it happened after the mysterious death of his lover’s husband, it may have had something to do with that. Other reports say it was because he threatened to kill the lawman’s family.)

Hardin was a native of Bonham, Texas, but was buried where he died. In 1996, his descendants tried to arrange to have him moved from El Paso to Nixon, where he had lived while married to his first wife. (They had three children.) According to an Associated Press report, they did it by just sort of … heading to the cemetery. They were stopped at the gates, as it were, and the entire matter ended up going to court. Hardin’s great-grandson summed up the family’s position, saying, “the memory of him is better served by people who knew what he was. He was a family man. He was a victim of the times, and he was viewed by many, many people as a friend.” It didn’t work, and Hardin remains in El Paso.

Billy the Kid’s legacy has lived on as a larger-than-life figure: Shot by Sheriff Pat Garrett, he was buried the day after he died, and the gravesite on the ground of Fort Sumner is marked with three names. Billy the Kid might be famous, but who are the other two people whose bones share his final resting place?

Thomas O’Folliard was Billy the Kid’s right-hand man, and was there when he was ambushed. Garrett killed him, too: After O’Folliard was shot in the chest, it took him about 45 minutes to die. Charlie Bowdre was only sort of tangentially associated with Billy the Kid, and just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when Garrett rode into town. After Bowdre was shot, he lay where he dropped for days before the burial of the three outlaws.

However, there’s a questionable theory that the man Garrett shot wasn’t Billy the Kid at all, and according to Daniel A. Edwards, author of “Billy the Kid: An Autobiography,” he actually lived to a ripe old age as Ollie “Brushy Bill” Roberts. “I now believe without a doubt that Billy the Kid was not killed by Pat Garrett in Fort Sumner,” Edwards explained (via Atlas Obscura). “I believe he lived, had many more adventures … before he finally died in Hico in 1950.” If that was the case, his bones are buried in Oakwood Cemetery, outside of Hamilton, Texas.

Life in the Wild West didn’t necessarily come with a promise of longevity, but when Wyatt Earp died at the ripe old age of 81, his Los Angeles Times obituary ran with the headline, “Wyatt Earp, Picturesque Gun-Fighting Marshal of Frontier Days, Passes Without Boots On.” His days of fighting cattle rustlers, outlaws, and gunslingers were far behind him, and instead, he had spent the last three years of his life fighting kidney disease.

By the time of his death, he had been living as the husband of Josephine Sarah “Sadie” Marcus for decades, even though no one has found evidence that they were ever officially married. It makes sense, then, that his cremated remains are buried alongside hers in her family plot, located in the Jewish area of the Hills of Eternity Cemetery.

Interestingly, in spite of the devotion the Earp brothers showed to each other in life, none are buried in the same cemetery. Morgan — who was killed a few months after the notorious OK Corral gunfight — was returned to his parents and buried in Colton, California’s Hermosa Gardens Cemetery. Virgil died of pneumonia in 1905 and was buried in Portland, Oregon, while James died of natural causes in 1926, and was buried in San Bernardino’s Mountain View Cemetery.

Sitting Bull had long been a voice of reason in the struggle against oppression, and was shot and killed in 1890. After his death, he was buried in a military-made coffin at Fort Yates, but that was perhaps unsurprisingly not the end of the story. When the construction of a nearby dam made it likely that his final resting place was going to be submerged beneath a lake, his descendants stepped forward to make it a not-so-final resting place.

Family requests to move Sitting Bull’s remains from South Dakota to North Dakota were rejected; not to be deterred, a group walked into Fort Yates, dug up the grave, then headed into North Dakota. Sitting Bull was reinterred in a vault overlooking the Missouri River … or, was he?

In addition to other rumors that he was taken to Canada, Fort Yates claims that the bones removed from their grounds weren’t Sitting Bull’s at all. That claim shed uncertainty on his final resting place, but there’s one more footnote. In 2007, the Smithsonian returned a lock of Sitting Bull’s hair to four siblings who have long claimed to be the leader’s great-grandchildren, and years later, DNA testing done on the hair confirmed Ernie LaPointe was Sitting Bull’s great-grandson. With that indisputable legal proof, he told NBC that he was hoping to move Sitting Bull’s remains to a site he was connected to in life, and re-bury him with proper honors. “He never got that privilege — he never got that — he was just buried in a box, you know?”

It seems like there could be little debate about the death of Jesse James. There are post-mortem pictures of him in a coffin, after all, but it turns out that there is a theory that James successfully faked his death. That aside, let’s talk about the mainstream remains.

James was famously shot and killed by members of his own gang in exchange for a pardon, and that’s what they got — along with the reward money promised to anyone who brought him to justice. James’s mother, Zerelda, turned down a $10,000 offer from someone looking to buy his remains, and instead had him returned to the James family home in Kearney, Missouri. He was buried there under a tombstone that read, in part: “MURDERED Apr. 3, 1882, By a traitor and coward whose name is not worthy to appear here” (via Smithsonian Magazine). He remained there for 20 years, until — amid worries over graverobbers — his family had him disinterred, positively identified, and moved to the city’s Mt. Olivet cemetery.

In spite of the fact that James’s mother instructed the family members who oversaw the moving of his remains to confirm to her that yes, it was still her son’s body in the grave, questions lingered. Fast forward to 1995, when researchers from George Washington University exhumed the grave for DNA testing, per The New York Times. After comparing it to known descendants, they confirmed that yes, it was still James in the grave.

After riding with the Dalton gang, Bill Doolin sharpened his train-robbing skills before forming his own gang and taking part in what’s believed to be the deadliest outlaws vs. lawmen gun battle in the Wild West. After a daring prison escape and about two months on the run, Doolin was shot and killed by a posse who caught up to him when he was visiting his wife and son.

And it was, indeed, the entire posse that brought him down on that August day in 1896, with at least eight men unloading their guns when he declined to accept their invitation to surrender. Interestingly, the gunshot wounds — which were mostly made by buckshot — were so unlikely-looking and suspiciously free of blood that early rumors suggested that he was dead when they caught up to him, and the scene was staged. That theory was short-lived, though: An examination of the body found that he had simply been so full of holes that he’d bled out pretty completely in the wagon he was thrown in. His heart alone had been pierced by no fewer than four bullets.

Doolin suffered one final insult when he was embalmed and displayed in what would be his final burial place of Guthrie, Oklahoma. He was finally buried in Summit View Cemetery’s Boot Hill section, and 81 years later, he would be joined by another outlaw who was more infamous in life than in death: In 1977, Elmer McCurdy — one-time train robber, one-time funhouse prop — was finally laid to rest beside him..